Today, almost every school in the U.S. has online learning as a part of its menu. Many parents are incorporating online education into their teaching toolkit at home, too. Unfortunately, some platforms have taken advantage of families during the pandemic, exploiting parents’ desire to provide the best possible education for their children during this difficult time. Prodigy is one of those platforms.

In February 2021, Campaign for Commercial-Free Childhood and 21 advocacy partners took action against Prodigy by filing a complaint with the Federal Trade Commission (FTC). Our complaint made headlines, raising awareness about Prodigy’s unfair practices. Even as we urge the FTC to ensure that Prodigy is held accountable for exploiting families on a national scale, our kids also need you to start the conversation about removing the game from your own school’s curriculum. We‘re inviting families, educators, and school leaders to say NO to Prodigy.

Prodigy is a math game used by millions of students, parents, and teachers across the globe. The game is designed for 1st through 8th graders to play during the school day and at home. In this online role-playing game, children create customized wizard characters to earn stars and prizes for winning math “battles,” finding treasure, and completing a variety of non-math challenges throughout the game. Children can also shop with Prodigy currency, practice dance moves, chat with other players, and rescue cute pets.

Prodigy is intentionally formulated to keep kids playing for long periods of time, but not for the reasons that we might hope. Instead of being designed to get kids excited about math, Prodigy is designed to make money. Prodigy claims it is “free forever” for schools. However, as children play one free version in the classroom they are encouraged to play a different free version at home. This home version, though technically “free,” bombards children with advertisements and uses relentless tactics to pressure children to ask parents for “premium” memberships, which cost up to $120 per child per year plus tax. As of September 2021, Prodigy also introduced an “Ultimate” membership priced at over $180 per year, further stratifying membership.

At first glance, Prodigy seems like a fun way to interest children in math. In reality, it jeopardizes children’s relationships with learning at a time when so much is already working against their success. It’s bad enough when manipulative gamified apps are marketed to parents as teaching tools in out of school time. But Prodigy is actually assigned by schools, making gamification and virtual shopping a required part of the curriculum while creating inequities in children’s math education.

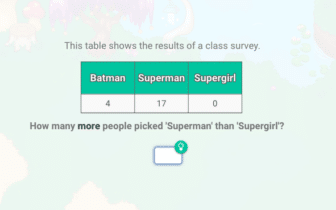

Prodigy’s push to sell Premium memberships is relentless, and aimed at kids. In just 19 minutes of “studying,” we saw 16 ads for membership and only 4 math problems. Ads take the form of videos and news feeds that showcase what Premium members can do that players without a membership cannot.

Premium memberships do not provide kids with access to a better learning tool. Instead, these memberships provide kids with bragging rights and digital goodies like cool hats and cute pets.

Although Prodigy’s math lessons are poorly integrated into the game, missing opportunities for students to make connections, the same cannot be said of its manipulative upselling tactics. Kids without Premium memberships are constantly reminded of their “lesser” status. For example, kids without memberships literally walk in dirt while kids with memberships ride around on clouds.

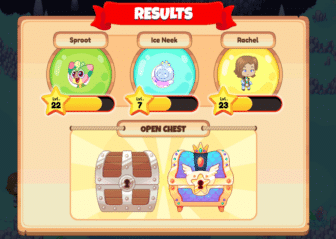

Prodigy’s tactics for selling Premium memberships also exploit kids’ curiosity. When kids finish a math battle they are presented with two treasure boxes: a plain wooden one and a sparkly blue one. When kids without Premium memberships click on the sparkly blue box, their choice is denied and they are blocked from finding out what’s inside. Instead, they are presented with an ad for a Premium membership, and kids who don’t upgrade at that moment must settle for the wooden box.

This constant upselling and manipulation is baked into a platform that over 90,000 schools have assigned as homework. Prodigy’s tactics are making students feel inferior because their parents haven’t paid for their math curriculum.

“Prodigy doesn’t belong in schools. By definition, public schools should provide all students equal access to whatever materials they offer. While there’s no credible evidence that any form of Prodigy effectively teaches kids math, it’s grossly unfair, and cruel, for the company to pressure kids and parents to buy a paid version by claiming that it’s more educational, or better in any way, than the game’s free version.”

“Prodigy doesn’t belong in schools. By definition, public schools should provide all students equal access to whatever materials they offer. While there’s no credible evidence that any form of Prodigy effectively teaches kids math, it’s grossly unfair, and cruel, for the company to pressure kids and parents to buy a paid version by claiming that it’s more educational, or better in any way, than the game’s free version.”

-Susan Linn, Ed.D., CCFC Founder and Author of Consuming Kids: The hostile takeover of childhood

Prodigy’s ever-present ads, both explicit and implicit, distract kids from learning math. For example, over a 19 minute period we saw 16 unique advertisements for membership, as well as opportunities to see ads via shopping and social play… and only 4 math “battles.” That’s four times as many ads as math learning opportunities.

In addition to the onslaught of ads, many of the in-game distractions are emotionally manipulative. Offers to rescue creatures, try new styles, chat with strangers, or try out new dance moves are hard for kids to resist.

Even research funded by Prodigy found that students tend to “wander about,” and that the “in-game distractions” (i.e. shopping, character customization, and advertisements) are a drawback. Teachers and administrators from the schools in the study acknowledged that extra math practice is important, but did not attribute any of their students’ achievement to Prodigy.

“Research has shown that rewards tend to undermine people’s interest in whatever they were rewarded for doing. A game like Prodigy may seem innocuous, or even fun, but by dangling the equivalent of doggie biscuits in front of kids for memorizing math facts — which is very different from helping them to make sense of mathematical ideas — the result is likely to be diminished curiosity about math itself. It’s sugar-coated control and it teaches kids that math is something they have to be bribed to do, not something they’d want to do.”

“Research has shown that rewards tend to undermine people’s interest in whatever they were rewarded for doing. A game like Prodigy may seem innocuous, or even fun, but by dangling the equivalent of doggie biscuits in front of kids for memorizing math facts — which is very different from helping them to make sense of mathematical ideas — the result is likely to be diminished curiosity about math itself. It’s sugar-coated control and it teaches kids that math is something they have to be bribed to do, not something they’d want to do.”

Prodigy does not incorporate math learning in to the fun parts of the game. Instead, Prodigy’s actual math components are essentially the same rote memorization that you can find on worksheets anywhere. Though Prodigy’s professed mission is “to help every student in the world love learning,” the lesson kids are more likely to learn is that math is boring on its own.

Prodigy could have embedded math into the plot of the game. For instance, it could invite characters to figure out the number of 1-foot planks needed to escape across a 7-foot ravine or to determine how many containers of food they need to collect to feed the pets they get while playing.

With the game as is, children don’t see how math matters in their character’s life, let alone their own. Math doesn’t become meaningful for students; Prodigy won’t help them to understand the process and concepts that are critical to effective math education.

Children learn to love the game and tolerate the math.

Most of a child’s attention is drawn not to math but to their character’s customization. In time considered independent learning, kids are buying and earning new accessories for their wizard and performing dance moves completely unrelated to the game’s plot. Children spend the most time in Lamplight Town, an outdoor mall. There, children can spin wheels to get more stuff and there are shops constantly available throughout the game—a known real-world sales tactic.

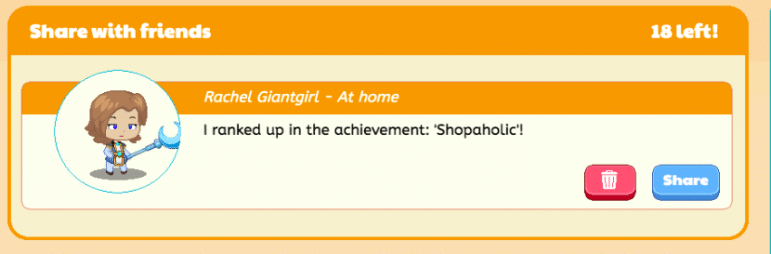

Members ride around on clouds, their flashy costumes and member badges gleaming while those with the free program wear plain clothes. That isn’t just a private feature. Children can see what their friends are wearing, making it clear who has a premium membership and who does not. Prodigy often uses social comparison as part of its relentless pressure on kids to buy new outfits or change their looks.

One social media-style feature, called “Wizard Watch” even reports on what other players have purchased while pop-up ads encourage children to keep up with their friends.

Prodigy pressures each child to customize their character by purchasing a membership. Given the emphasis on shopping and socializing, how do they get away with calling Prodigy a math game?

When schools assign Prodigy, they create two tiers of students: those whose families can afford to buy a membership, and those whose families can’t. Prodigy’s model is the equivalent of giving wealthy kids in a classroom a shiny new textbook with a surprise toy inside, while kids from low-income families get an old, beaten-up edition. And as kids play, they can tell who are the haves and have-nots.

Children with a Premium membership advance in the game faster, earning higher scores from completing the same tasks. Students whose families’ can afford the membership appear to be better at math than children without the membership who are left with a lower score. In a research study on Prodigy’s effectiveness, students recognized unfairness in the additional rewards that members receive, stating “their least favorite component is that some students have memberships while others do not” (p. 17). These messages of relatives success can be problematically internalized by students and teachers alike.

As more and more schools require students to play Prodigy as part of their curriculum during remote learning, those inequities become baked into math class. Our students don’t need any more factors working against them—especially during a pandemic.

Mixed Messages

Prodigy lures parents and schools by falsely claiming the game is “free forever.” Actually, the platform’s model is built on convincing kids they need to spend money on the game.

Prodigy tells parents they need to shell out for their paid version to boost their children’s math skills. But when pressed, they claim the free version is an equally effective tool.

Prodigy tells teachers that using the app to engage some students will give instructors more one-on-one time with kids—but teachers say students still need support and attention to succeed while playing Prodigy.

“Like sugary cereal, Prodigy is designed to attract kids. It is a highly-engaging video game filled with revenue-generating devices masquerading as tools for math practice. Prodigy capitalizes on the desires of caregivers and educators to support kids’ achievement, and despicably monetizes kids’ desire to feel admired and included by their peers. All kids deserve to practice math without enduring virtual distractions designed to shame or otherwise prod them into nagging their caregivers for memberships priced high enough to break many family budgets.”

“Like sugary cereal, Prodigy is designed to attract kids. It is a highly-engaging video game filled with revenue-generating devices masquerading as tools for math practice. Prodigy capitalizes on the desires of caregivers and educators to support kids’ achievement, and despicably monetizes kids’ desire to feel admired and included by their peers. All kids deserve to practice math without enduring virtual distractions designed to shame or otherwise prod them into nagging their caregivers for memberships priced high enough to break many family budgets.” Prodigy is designed to promote prolonged engagement with the game, not to get kids excited about math. When we observed an 8-year-old playing, for example, she spent almost the entire time engaged in non-math activities—shopping, digging for bones, looking at her pets. Prodigy’s bells and whistles lure children into staying on the game longer, but actually hinder math learning.

Prodigy is designed to promote prolonged engagement with the game, not to get kids excited about math. When we observed an 8-year-old playing, for example, she spent almost the entire time engaged in non-math activities—shopping, digging for bones, looking at her pets. Prodigy’s bells and whistles lure children into staying on the game longer, but actually hinder math learning.

Prodigy’s own research says a child would have to answer 888 Prodigy math questions to raise their standardized test math score by one point. Our investigation found that children would need to play more than twelve focused hours to answer that many questions! And that’s only if they don’t get distracted by the game’s other features (which are, as we know, built to distract). For kids drawn to Prodigy’s bells and whistles, it may take as many as 30 to 40 hours of screen time to make minimal improvement on a standardized test.

Children deserve math tools that get them excited about learning, not just trick them into staying on screen.

“Prodigy may keep children quiet and happy while teachers or parents are busy, but it doesn’t teach them math. Research indicates that kids must spend hours in the game to improve their math achievement scores by just one point. That might not be so terrible, perhaps, but during those hours they endure emotionally abusive marketing until they convince their parents to shell out money for a membership. Under a pretense of teaching math, Prodigy is using schools to access and manipulate a lucrative child market.”

“Prodigy may keep children quiet and happy while teachers or parents are busy, but it doesn’t teach them math. Research indicates that kids must spend hours in the game to improve their math achievement scores by just one point. That might not be so terrible, perhaps, but during those hours they endure emotionally abusive marketing until they convince their parents to shell out money for a membership. Under a pretense of teaching math, Prodigy is using schools to access and manipulate a lucrative child market.”

-Faith Boninger, Commercialism in Education Research Unit, National Education Policy Center, University of Colorado Boulder

Prodigy uses an industry-funded research study from Johns Hopkins University to back up its claims that it increases math achievement and self-confidence. Even Prodigy’s own study revealed that teachers and students found major flaws with the game. Not only were teachers and principals “reluctant to attribute student achievement to Prodigy,” (p. 25) the study encourages teachers to apply time limits to the in-game distractions like shopping and avatar customization. Furthermore, the game draws kids to the screen but the data suggests that “more and more usage of Prodigy may not result in more and more achievement” in math understanding (p. 26).

Prodigy’s website tells different, contradicting tales about the game. It tells parents that their kids need a membership to be better at math, but tells schools that the membership doesn’t matter. Prodigy shows teachers one version of its game—without membership ads—but when kids play from home, they get another, full of endless distractions—advertisements and lures for shopping, character customization, social opportunities, and more. Teachers who assign children to use Prodigy at home may not even know their students are getting a completely different version of the game! Meanwhile, because it’s assigned, parents believe that it’s a good tool for learning and quality screen time.

During the pandemic, children are using Prodigy at home more than ever, which means they’re not getting the supervision they may need to learn while playing, and they’re being bombarded with advertisements. Prodigy has taken advantage of the pandemic, preying upon schools’ distance learning needs to sell memberships.

“Prodigy has been a source of conflict in our household since the 2 week free trial ended. When my kids started to play through their classes at school, they got an all access two weeks. Prodigy promises “no cost ever,” but after the 2 week trial is up, the game relentlessly tells kids to beg their parents to buy an annual membership. When they’re not giving a sales pitch, they’re distracting my kids with shopping. Members get two spins. Members get up scaled treasure boxes. Members get double stars and pets. Prodigy offers motivational math practice but what we really get is an education in targeted advertising.”

–Katrina S., parent, Alberta, Canada

Take Action: Let’s say “NO” to Prodigy.

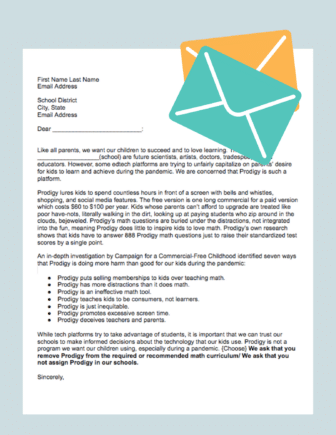

How can you help get Prodigy out of schools? We have provided you with a letter template to help make your school district aware of Prodigy’s negative impacts. Additionally, you can share our social images, videos, and this page to let people know how not to settle for children’s “learning” via games like Prodigy.

Write to your school or district.

Has Prodigy hoodwinked your school into thinking its good for kids? Share your concerns with your school district. Download our letter template to help make your voice heard, and talk to your child’s teacher about the game! Your voice makes a difference in helping schools to rid themselves of programs like Prodigy that work against our kids.

Download and share these images on social media.

Download these images to share on your social media page and follow us on Facebook and on Twitter @commercialfree for updates and more!

Follow our advocacy.

We’ve spoken out, too! In fact, in February, we wrote a letter to the Federal Trade Commission asking them to examine Prodigy’s practices. Twenty-one other advocacy groups also signed on. We know that parents and teachers aren’t to blame when big companies come after kids, and we’re doing our part to hold Prodigy accountable. Stay tuned via our social media or by joining our mailing list for updates!

Share your experience with us.

Let us know how your efforts go! Reach out via email and tag us on social media using the hashtag #SAYNOTOPRODIGY so we can show our kids that we believe they deserve better.