This is part 3 of our Safe, Secure, & Smart Guide to Choosing Tech for Your Preschooler. To learn more about this series and read our guides about online videos and apps click here.

“Alexa, are you good for me?”

Connected toys and devices (like smart speakers and AI toys) can provide families with conveniences from voice-activated timers to instant facts to responding to that question whose answer is on the tip of your tongue (“who was that one actor in that one show?”). In fact, over 40 million homes have these devices. But, they can have deep negative consequences for our families (and especially for very young children).

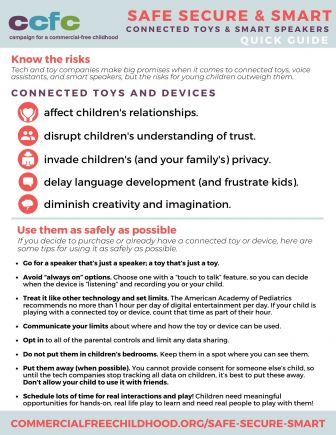

We rarely tell families not to use a form of technology at all. Yet, there are some devices that pose so much risk to children’s privacy and wellbeing that the best approach is just to say, “no!” We believe families should not use Internet-connected toys and devices with young children. We also know that many families already have them, and we’re here to help!

In this guide, we’ll take you through the two most common types of internet-connected items used by young children (smart speakers and AI toys), explain the risks, and discuss how to minimize these risks if you decide to purchase one.

The promises of smart devices and toys.

Sometimes, we think that smart speakers and toys are better tech options for children’s play and learning because they are screenless. While they don’t have the blue light impact that screens do on our vision1, they raise many of the same concerns. These devices monopolize children’s time and attention, they collect a lot of data about kids, and they use that data to create commercialized and personalized content for kids, undermining their personal creative growth and learning. Tech companies and marketers work really hard to hype the so-called “benefits” of these devices in hopes of overshadowing the risks.

Smart Speakers

Smart speakers (both adult and kid versions) are inherently risky. Always on and listening, these devices record the happenings of your home including everything from children’s play to their tantrums. These conversations hold clues about where you’re going and what you’re doing, even when you’re away from the speaker.

- Amazon Echo/ Amazon Echo Kids

- Google Plus

- Siri/Cortana/Tablet Voice Assistants

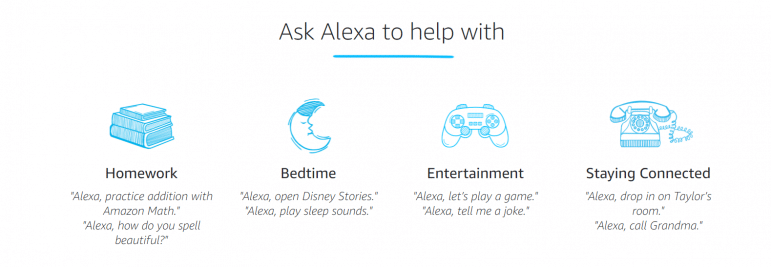

Most of these devices offer features like weather forecasts, music, timers and alarms, recipes, games, facts and “homework help,” phone calls and connectivity, and hundreds of downloadable “skills” or features.

One device that really concerns us is Echo Dot Kids, the kid-targeted version of Amazon’s “Alexa.” Amazon claims that the Echo Dot Kids “is packed with skills and features that help kids learn and grow every day.”2 Yet, there is no empirical evidence that this type of device advances learning.

Connected Toys

Of all the tech devices for kids from tablets to switches to phones, if there’s one we suggest you ditch outright, it’s any internet-connected toy. These toys are creepy, and they can really interfere with children’s development. Some of the toys that fit this category include:

- Moxie Robot

- Cognitoys Dino

- KidKraft Amazon Alexa Toy Kitchen

- Hotwheels ID Smart Track Kit

- My Friend Cayla (discontinued)

- Spiral Toys’ CloudPets (discontinued)

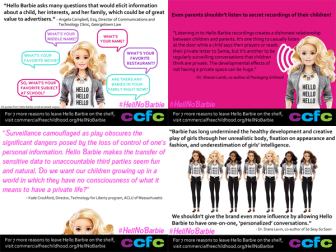

- Hello Barbie (discontinued)

Connected toy makers often claim that these toys are “educational,” offering social interactions, opportunities to learn facts, and wholesome fun. For example, Moxie Robot’s makers claim that the toy is a “revolution in child development,” provides “major advantages to social-emotional learning skills,” and provides “meaningful play, every day.”3 Some of the most popular toys in the past decade have been discontinued or cancelled because they violate privacy and security concerns, but that still hasn’t prevented more of these creepy products from continuing to crop up.

Impacts of connected toys and devices on our kids

All of the claims made by these technology and toy companies have been refuted by research and experts across the globe. Preschool children are particularly vulnerable to devices like these, as they can negatively impact how and what children can learn, their relationships, creativity, language ability, and values. Here are some of the ways that the features of these products can harm children:

They affect children’s relationships.

Preschoolers learn best from hands-on play and real-life interactions with others, especially the adults in their lives. In fact, one of the main pillars of learning requires other real humans to interact positively with a preschooler in order for them to learn.5 MIT professor and author of Reclaiming Conversation Dr. Sherry Turkle warns, “Children form artificial relationships with internet-connected devices at the expense of real relationships with people.”6

When researchers looked at how children interact with connected toys, they found that they were likely to treat them like a person7. Another study “observed that… young children…attributed human-like qualities to the devices and developed an emotional attachment to them.”8

Preschoolers easily build what are called “parasocial relationships” with tech, defined as “one-sided, emotionally tinged friendships that develop between an audience member and a media character.”9 These characters include “Alexa,” “Siri,” “Google,” robot toys, and connected dolls and stuffed animal toys. These are more complicated than a child loving a Sesame Street character because the toys or devices actually talk back, but of course do not offer the trust and reciprocity that real relationships do.

While some may hope that these parasocial relationships can promote positive, prosocial behaviors in children, in reality, these devices most often promote brands, consumerism, and the racial, class, and gender stereotypes far too often associated with consumer culture. And while kids may feel like they are talking to a friend, they are in essence talking to a corporation who is more interested in their data and money.

For example, there’s a big difference between a kid’s relationship with an old-fashioned teddy bear and a relationship with an AI toy or device. With a regular teddy bear, a child sets the agenda for play. They talk to the bear as a friend, and any “talking” the bear does comes from the child as well; in other words, the bear, through the choices of the child, does what the child needs it to do in order to carry out an idea, process a concept, or try out a new role. Children need this type of experience to make sense of the world and to form their identities. They need the teddy bear to do what they say.

With AI devices, it’s the other way around. The devices direct the play and conversations. For example, talking to Hello Barbie often consists of a child answering a bunch of Barbie’s questions rather than true back and forth. And sometimes, Hello Barbie changes the subject abruptly. (“So now that we’ve been using our imagination and played games, let’s get serious and talk about something really important…FASHION!”)10 The toy’s agenda is not what’s best for your child; it’s what’s best for Big Tech.

When children develop trusting relationships with technology (because at this age, that’s what they instinctively do), it can impact their social development tremendously. Ultimately, it’s not a good idea for children to have frequent interactions with AI devices like these because not only do they work against what preschoolers need to learn and thrive, but they detract and distract from what children get from play.

They disrupt children’s understanding of trust and invade privacy.

In one study of Amazon Echo, “75% of children ages 3 to 10 believe that Alexa always told the truth.”11 And as young children develop relationships with these devices, their trust grows, opening the door to marketers, corporations, and strangers.

These products normalize surveillance culture. Children feel like it is okay to be always watched by strangers.12 Amazon Echo will “instantly drop in on [the kids’] room to remind them it’s bedtime. Or, let everyone know dinner is ready by making an announcement to every room that has a compatible Echo device.”13 With a setup like this, parents can always listen in on their children’s play and conversations, but so can the marketing algorithms programmed into Alexa.

There’s a big difference between listening to your child from the doorway and listening through a speaker or recording. For one, when you’re nearby and visible, you’re observing your child, not spying on them. Researchers also found that young children do not understand the surveillance aspects of connected toys and devices; they don’t know they’re being recorded.14

But more importantly, when you use a connected device or toy, whatever is said to the device is immediately translated into text and stored. That text is then analyzed by machines to create a profile for your child (which then is [illegally] used to market future things to your child and build their brand loyalty). That data can then be accessed by even more different people and is often sold to third parties such as marketing firms that have contracts with Amazon. Generally, the companies won’t say who the third parties are, so what’s happening with your child’s data is a worrisome mystery.

And that’s only if things go as planned. In addition to this planned sharing of data, hackers may be able to access recordings of your child or even communicate with your child through a device like the ones listed above. In 2017, when CloudPets stuffed animals were hacked, the hackers held the voice recordings of children as ransom.15 The now-retired My Friend Cayla doll could be hacked by anyone just using their smartphone – meaning any stranger standing outside of the child’s house could talk to the child through the doll. And, thankfully, CCFC’s advocacy in 2017 prevented the release of Mattel’s Aristotle, which was an always-on baby monitor that gave corporations round-the-clock access to children’s eating, sleeping, and play. Talk about creepy!16

Children put their trust in these toys and devices, but devices don’t keep secrets. These “toys” put kids in harm’s way for the sake of profit.

Privacy Not Included

- Uses encryption

- Requires strong passwords

- Has a system to manage vulnerabilities

- Has an accessible privacy policy

They delay language development (and frustrate kids).

It is normal for young children to have communication breakdowns with adults and peers. In fact, toddlers and young preschoolers are unsuccessful in communicating an idea the first time around two-thirds of the time17. What helps them develop is when their peers and adults help them to work through it to get their idea across.  Internet connected devices will never suffice because “recognizing and correcting communication breakdowns is an essential part of young children’s interactions with the world.”18 This process of clarifying is known as “communication repair.”

Internet connected devices will never suffice because “recognizing and correcting communication breakdowns is an essential part of young children’s interactions with the world.”18 This process of clarifying is known as “communication repair.”

But unlike a caring adult, technology can’t offer communication repair. Studies document how young children frequently get frustrated when interacting with smart toys and devices.19 20 Usually, these frustrations occur because the device doesn’t understand what the child is saying. One study found children whose speech is not well understood spoke less, used fewer words, and were cut off by the smart devices, causing an interruption in their learning.21 This disrupts the necessary speech practice that young children need. It also creates additional challenges for English language learners or children with auditory or speech disorders.

The impacts of this don’t stop when a child disconnects from the device. In fact, researchers found that after children play with internet-connected toys, they are likely to interact with real people in the same way.22 More significantly, they communicate with the real people around them less, which further delays language development.23

Using them diminishes children’s creativity and imagination.

But, in reality, the toys hinder and limit creativity and true imagination. Amazon Echo’s “I’m bored” function is one example. As soon as children say “I’m bored,” Alexa will suggest a handful of games (all of which are associated with commercial characters or products). When children use Alexa to play games, the only options are commercialized games connected to Barbie, Dreamworks films, and other brands. These games have scripts that take the imagination out of what children are doing and instead put their learning into the context of a commercialized story. Young children have a hard time breaking out of these scripts once they’re stuck in them, and it can limit their ability to think creatively and problem solve later in life.25

And, while it may seem like a good thing to prevent boredom, boredom is actually necessary friction for young children. Children’s ability to entertain themselves and not take the easy route when it comes to getting what they want is related to their impulse control (their ability to plan and work toward what they want or need). Impulse control is a top factor in success later in life, including having meaningful relationships, getting good grades, and staying out of jail.26 27 So, when AI speakers and toys provide instant access to entertainment and facts, they displace the valuable problem solving, self-regulation, and creativity in children’s experiences, all of which are necessary for their well-being.

When children are surveilled, their play is also impacted.28 They act differently when they know they are being watched. Think of the way you feel when a friend all of a sudden starts filming you. Your attention shifts away from whatever you were doing, cutting off the full, embodied, engagement you felt before realizing you were being recorded. For children, the effect is amplified. Technology has the potential to stop the deep, meaningful play that child development experts say is critical for their brains, bodies, and emotions29 in its tracks.

When parents buy [a connected device or toy] they set themselves up for two bad choices. They can decide not to tell their children that [the tech company] is secretly listening to them, a deception that colludes with the toy company as it spies on their child. How will the children feel about this when they get older?

Conversely, they can tell their children the toy company is listening in, which could make their kids self-conscious, set them up to perform for an invisible audience or otherwise alter their natural play. This will also teach their children that it is fine to have large corporations monitoring their behavior.”

-Allen Kanner, PhD, child psychologist and author of Psychology and Consumer Culture

They track more than just your family: The “playdate problem”

Smart devices not only track your family, but anyone you invite in your home. While you might accept a device like Amazon Echo Dot Kids tracking your own child (although we hope you won’t!), every family should have the right to consent before making recordings of their child. So if you do allow your child to play with a connected device, make sure you unplug it and put it away when your children’s friends come over.

Using connected toys and devices as safely as possible

Ultimately, we recommend avoiding these devices entirely, especially if you’re explicitly using them with your preschooler. However, if you do decide to get one (or you already have one), here is our advice for moving forward.

Go for a speaker that’s just a speaker; a toy that’s just a toy. The biggest issue with these items is their ability to record you and your children. Go for a Bluetooth speaker that’s just a speaker or a toy that’s just a toy. See our side bar for some toys we recommend.

Avoid “always on” options. Choose one with a “touch to talk” feature, so you can decide when the device is “listening” and recording you or your child.

Treat it like other technology and set limits. The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends no more than 1 hour per day of digital entertainment per day.30 If your child is playing with a connected toy or device, count that time as part of their hour.

Communicate your limits about where and how the toy or device can be used.

“We are going to use our Alexa for playing music and setting timers only.”

“Oops! Let’s keep these in the kitchen. It’s not safe for them to be in your room.”

“Let’s not use the ‘I’m bored’ game. Let’s see what other ways we can be creative today!”

Opt in to all of the parental controls and limit any data sharing.

Do not put them in children’s bedrooms. Keep them in a spot where you can see them.

Put them away (when possible): You cannot provide consent for someone else’s child, so until the tech companies stop tracking all data on children, it’s best to put these away. Don’t allow your child to use it with friends.

Schedule lots of time for real interactions and play! Children need meaningful opportunities for hands-on, real life play to learn and need real people to play with them!

If you can, transition your child away from it. Before you get rid of it, see if you can clear your data from it.

Additionally, here are some suggestions specific to each type of tech:

Smart Speakers/ Voice Assistants

- Change Alexa’s name to “Computer.” It’s subtle, but having a human name for this device could further exacerbate the trust and parasocial relationship issues.

- If you’re getting a smart speaker, buy one like Sonos which is just that: a smart speaker that connects to your phone (and doesn’t record you).

- Avoid the “I’m bored” functions as it is essential that children learn to rely on themselves, not corporations, to alleviate boredom.

AI Toys

- Have regular conversations about how the toy is an electronic, internet-connected toy. “Remember, this is a toy. It doesn’t have feelings like you do and it uses a computer, not a brain, to talk back to you.”

- Talk to your child about the toy and its features. Use words like “This is a different kind of toy. It records us and mama can hear you when you’re playing.”

- Take out the batteries or don’t charge them! All toys are better when children can use their imaginations.

The best toys for kids

- Boxes

- Arts materials (crayons, paper, paint, markers, string, etc.)

- Puzzles

- Blocks

- Pots, pans, and containers

- Dolls and people figurines

- Clean recycling (toilet paper tubes, caps, tissue boxes, etc.)

- Cars and trains

- Musical instruments (shakers, tambourines, etc.)

- Sticks

- Rocks

Conclusion

Internet-connected toys and devices do not offer developmentally appropriate and safe opportunities for preschoolers. The risks are greater than ever with these products as technology companies look for more effective, sneakier ways to profit off of children. Because these products require a lot of work on families’ parts to keep their children safe, we strongly encourage you to avoid them.

CCFC continues to fight so that it’s not so hard to find products that don’t put your children in harm’s way. In fact, in 2019, we, alongside our friends at the Center for Digital Democracy, asked the FTC to investigate Amazon Echo because it was storing children’s data illegally, even after families had deleted recordings of their children.31 As a result of our complaint, Amazon changed their practices. Now it’s easier for you to delete your data (and keep it deleted). While this is just one small step, it signifies a bit of hope in building a safer digital world for kids.

We hope this guide has helped you to understand how to keep your child safe, secure, and smart when it comes to technology.

This project was made possible by a generous grant from the Rose Foundation for Communities and the Environment.

This project was made possible by a generous grant from the Rose Foundation for Communities and the Environment.

Need more tools? Check out these additional resources.

1The Vision Council. (2019). The Vision Council Shines Light on Protecting Sight – and Health – in a Multi-screen Era. Retrieved May 19, 2021, from https://www.thevisioncouncil.org/blog/vision-council-shines-light-protecting-sight-and-health-multi-screen-era

2Amazon.com. (2020). All-new Echo Dot (4th Gen, 2020 release) | Smart speaker with Alexa. https://www.amazon.com/dp/B07XJ8C8F5?ref=ods_ucc_aucc_DEVICECODEFIRSTLASTLETTER_nrc_ucc

3 Embodied, Inc. (2021). Embodied Moxie Robot. Embodied, Inc. https://embodied.com/

4 CCFC, & CDD. (2019). Request for Investigation of Amazon, Inc.’s Echo Dot Kids Edition for Violating the Children’s Online Privacy Protection Act (Echo Dot Complaint,Final). Retrieved from https://www.law.georgetown.edu/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/Echo-Dot-Complaint-FINAL-1.pdf

5 Hirsh-Pasek, K., Zosh, J. M., Golinkoff, R. M., Gray, J. H., Robb, M. B., & Kaufman, J. (2015). Putting Education in “Educational” Apps Lessons From the Science of Learning. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 16(1), 3–34. https://doi.org/10.1177/1529100615569721

6 CCFC, & CDD. (2019). Request for Investigation of Amazon, Inc.’s Echo Dot Kids Edition for Violating the Children’s Online Privacy Protection Act (Echo Dot Complaint, Final). Retrieved from https://www.law.georgetown.edu/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/Echo-Dot-Complaint-FINAL-1.pdf

7 Druga, S., Williams, R., Breazeal, C., & Resnick, M. (2017). “Hey Google is it OK if I eat you?”: Initial Explorations in Child-Agent Interaction. Proceedings of the 2017 Conference on Interaction Design and Children. Association for Computing Machinery, 595–600. doi:doi.org/10.1145/3078072.3084330

8 Garg, R., & Sengupta, S. (2020). He Is Just Like Me: A Study of the Long-Term Use of Smart Speakers by Parents and Children. Proceedings of the ACM on Interactive, Mobile, Wearable and Ubiquitous Technologies, 4(1), 1-24.

9 Jordan, A. B., & Romer, D. (2014). Media and the Well-being of Children and Adolescents. Oxford University Press.

10 Jones, M. L., & Meurer, K. (2016). Can (and should) Hello Barbie keep a secret? Paper presented at the 2016 IEEE International Symposium on Ethics in Engineering, Science and Technology (ETHICS). Retrieved from: https://science.sciencemag.org/content/359/6380/1146

11 Druga et al. (2017).

12 Mascheroni, G. (2018). Researching datafied children as data citizens. Journal of Children and Media, 12(4), 517-523. doi:10.1080/17482798.2018.152167

13 Amazon.com. (2020). All-new Echo Dot (4th Gen, 2020 release) | Smart speaker with Alexa. https://www.amazon.com/dp/B07XJ8C8F5?ref=ods_ucc_aucc_DEVICECODEFIRSTLASTLETTER_nrc_ucc

14 McReynolds, E., Hubbard, S., Lau, T., Saraf, A., Cakmak, M. Roesner, F. (2017) Toys that Listen: A Study of Parents, Children, and Internet-Connected Toys. Proceedings of the 2017 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems. https://doi.org/10.1145/3025453.3025735

15 Hunt, T. (2017). Data from connected CloudPets teddy bears leaked and ransomed, exposing kids’ voice messages. Troy Hunt. https://www.troyhunt.com/data-from-connected-cloudpets-teddy-bears-leaked-and-ransomed-exposing-kids-voice-messages/

16 Campaign for a Commercial-Free Childhood. (2017). Victory! Mattel cancels spying AI device for babies & kids. Campaign for Commercial Free Childhood. https://commercialfreechildhood.org/victory-mattel-cancels-spying-ai-device-babies-kids/

17 Cheng, Y., Yen, K., Chen, Y., Chen, S., Hiniker, A. (2018) Why Doesn’t It Work? Voice-Driven Interfaces and Young Children’s Communication Repair Strategies. In Proceedings of the 17th ACM Conference on Interaction Design and Children. Retrieved from http://faculty.washington.edu/alexisr/quack.pdf

18 Cheng et al. (2018), ibid.

19 Druga, et al. (2017), ibid.

20 McReynolds, et al. (2017), ibid.

21Monarca, I., Cibrian, F. L., Mendoza, A., Hayes, G., & Tentori, M. (2020). Why doesn’t the conversational agent understand me? A language analysis of children’s speech. Adjunct Proceedings of the 2020 ACM International Joint Conference on Pervasive and Ubiquitous Computing and Proceedings of the 2020 ACM International Symposium on Wearable Computers, 90–93. https://doi.org/10.1145/3410530.3414401

22 McReynolds et al (2017), ibid.

23 Healey, A., & Mendelsohn, A. (2019). Selecting Appropriate Toys for Young Children in the Digital Era. Pediatrics, 143(1). doi:10.1542/peds.2018-3348

24 Amazon.com. (2020). All-new Echo Dot (4th Gen, 2020 release) | Smart speaker with Alexa. https://www.amazon.com/dp/B07XJ8C8F5?ref=ods_ucc_aucc_DEVICECODEFIRSTLASTLETTER_nrc_ucc

25 Linn, S. (2009) The Case for Make Believe: Saving Play in a Commercialized World. The New Press.

26 Schlam, T. R., Wilson, N. L., Shoda, Y., Mischel, W., & Ayduk, O. (2013). Preschoolers’ delay of gratification predicts their body mass 30 years later. The Journal of pediatrics, 162(1), 90-93.

27 Beder, S. (2009). This little kiddy went to market: The corporate capture of childhood. New York, NY: Pluto Press.

28 Kanner, A. (2020). Personal Communication.

29 Carlsson-Paige, N. (2018). Our Latest Report: Young Children in the Digital Age: A Parent’s Guide. Defending the Early Years. Retrieved November 17, 2020, from https://dey.org/publication/our-latest-report-young-children-in-the-digital-age-a-parents-guide/

30 Council on Communications and Media. Media and young minds. Pediatrics. Nov 2016, 138 (5) e20162591; DOI: 10.1542/peds.2016-2591

31 CCFC, & CDD. (2019), ibid.